Optimized Health

and Longevity

Our communities will have access to the health care, community services, and caregiver supports needed as we age.

Health and well-being must address the complete person and include equitable access to quality care and services.

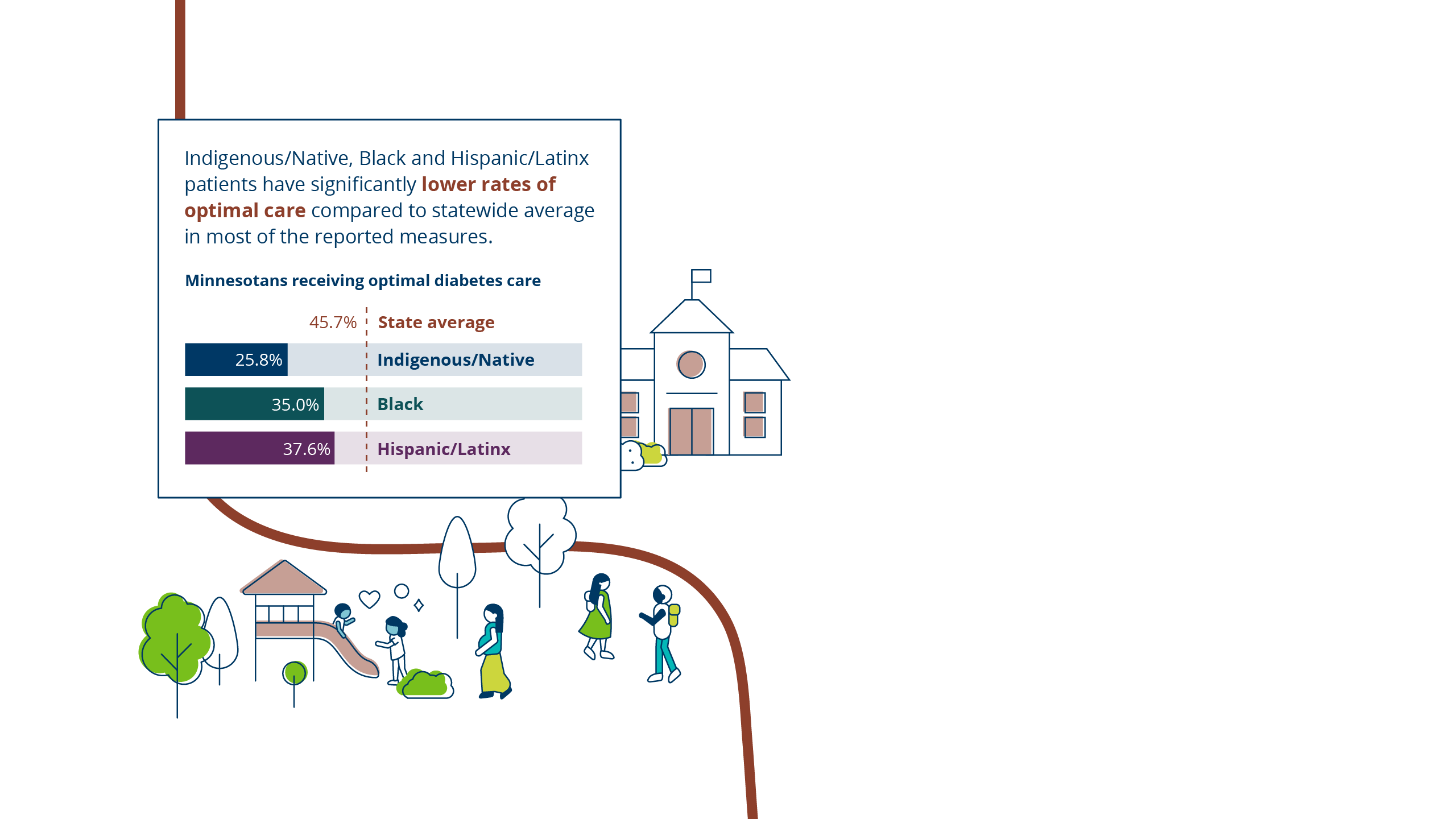

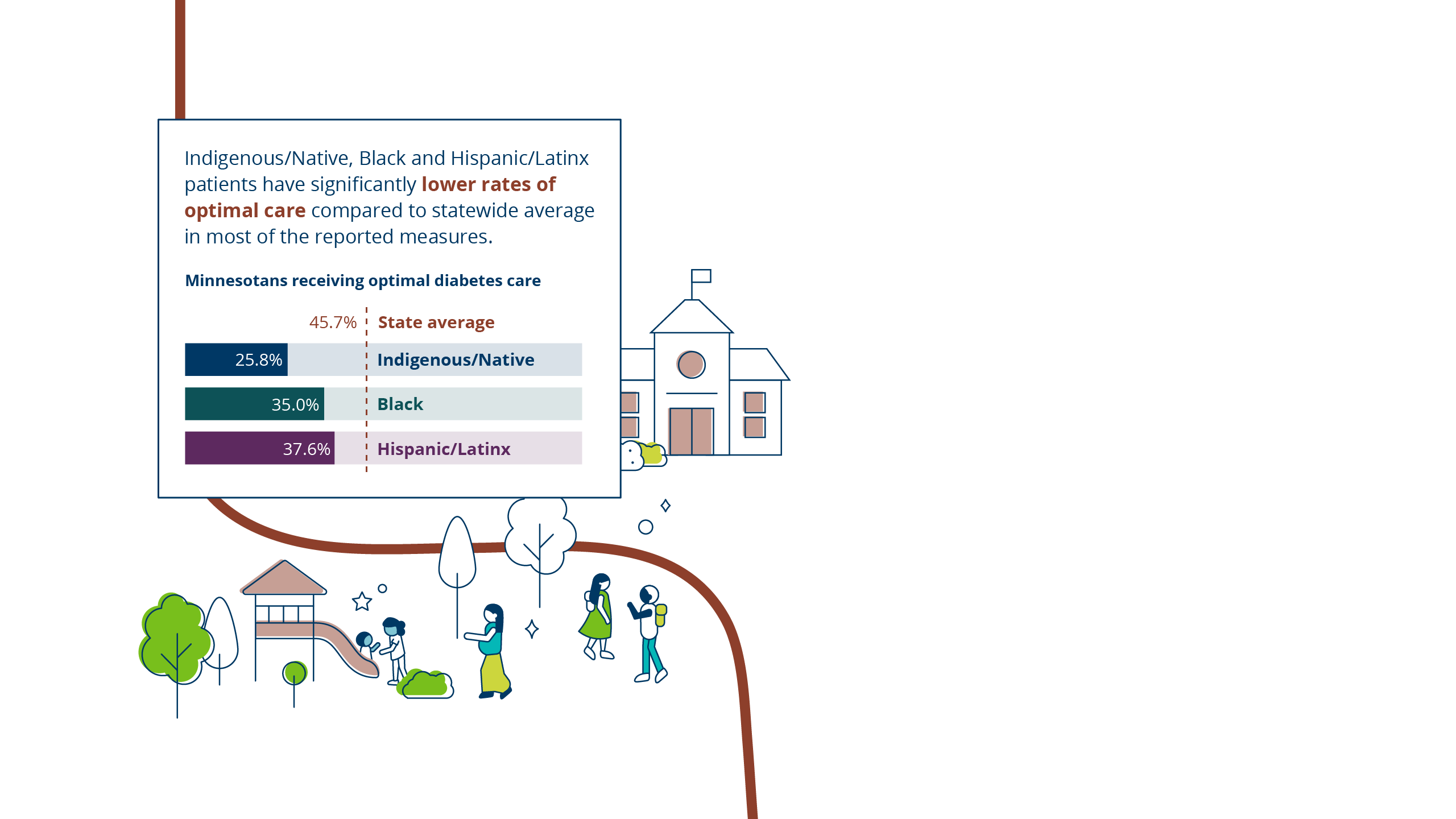

As they say: live long, die short. Today, the average Minnesotan lives to be around 80 years old. However, notable disparities in life expectancy as well as quality of healthcare and health outcomes exist across race and similar factors. How can prevention and the care and services we all receive help us live not only longer, but live well in later life?

To achieve this goal, our strategies are:

- Integrated Care, Health, Services, and Social Supports

- Support for Family, Friend and Neighbor Caregiving

- Health Promotion

- A Thriving Direct Care Workforce

How can all of us age with equitable opportunities for optimal health?

Integrated Care, Health, Services and Social Supports

Person-centered, coordinated care can address the big picture of a person’s life and well-being.

This integrated approach is anchored in what matters to the person. It recognizes the biological, psychological, and social parts in each of us, and how they are connected. Doctors, nurses, psychologists, social services, long-term care, and others involved work together to provide optimal care for an individual, and ensure that person’s wishes are at the center.

Integrated, person-centered care is even more important as we get older and are likely to have more complex health. Minnesota is already taking steps in this direction. We can bolster these strategies in our state with particular attention to how they can benefit us all as we get older.

Support for Family, Friend and Neighbor Caregiving

We need each other as we age.

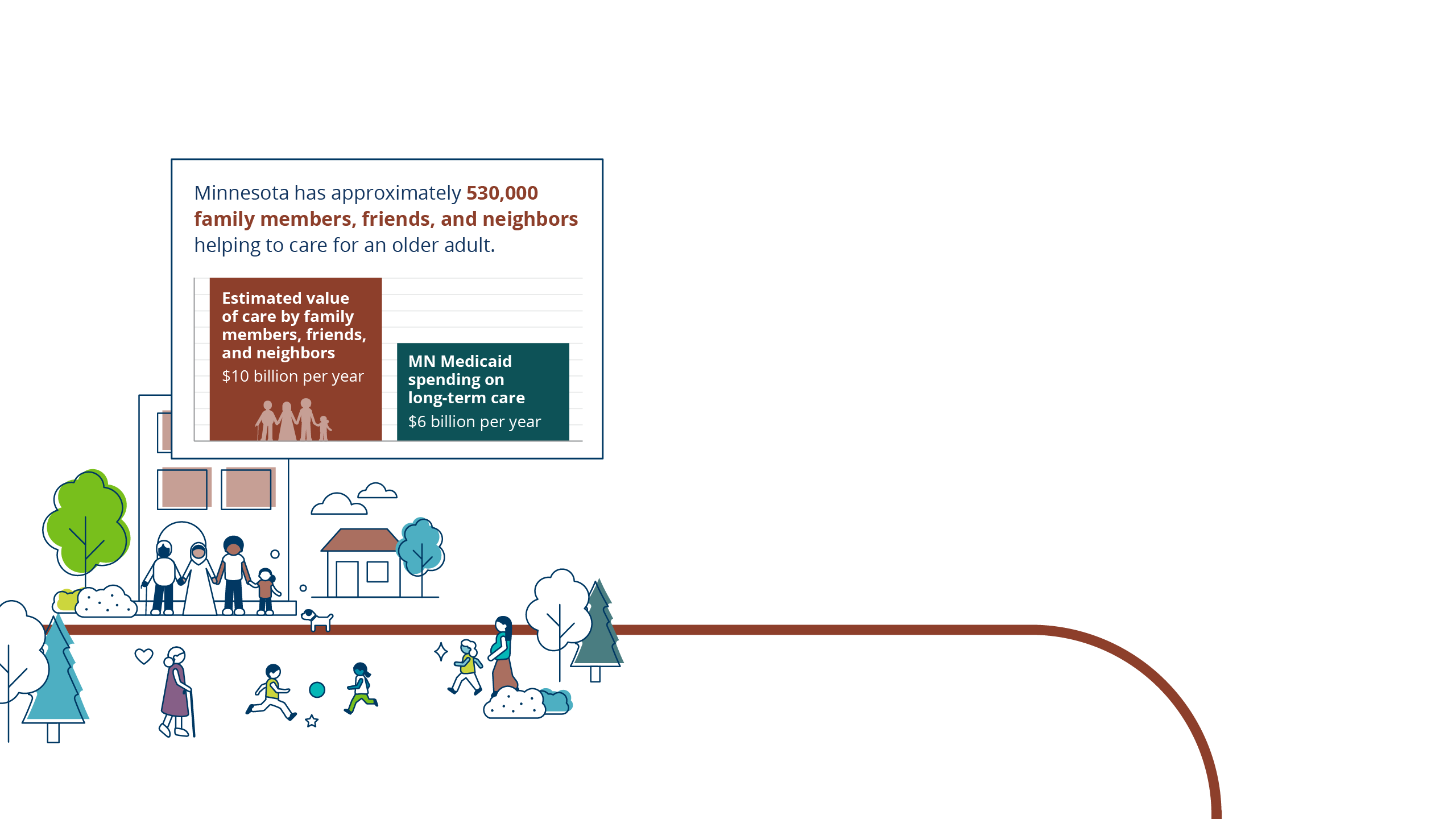

Family, friend, and neighbor caregiving is a backbone of Minnesota’s healthcare system. Minnesota has approximately 530,000 family, friends, and neighbors helping to care for an older adult1—in many cases making it possible for a person to remain living at home. More than 1 in 5 of these caregivers supports someone with a form of dementia.2

Minnesota’s investments in caregiving and dementia are significant and commendable, but additional investments and coordinated efforts will be needed to meet growing needs.

This must include inclusive, respectful supports for our increasingly diverse population, recognizing that cultural norms and expectations vary widely when it comes to aging.

Health Promotion

All of us deserve quality, unbiased, respectful medical and other care, including as we age. Ageism—one of the least acknowledged forms of discrimination—is widespread in healthcare and has vast human and economic costs.3 New models, such as Age-Friendly Health Systems, Geriatric Emergency Rooms, and Age-Friendly Public Health, are spurring systemic shifts in how the health field approaches older patients and aging in general.

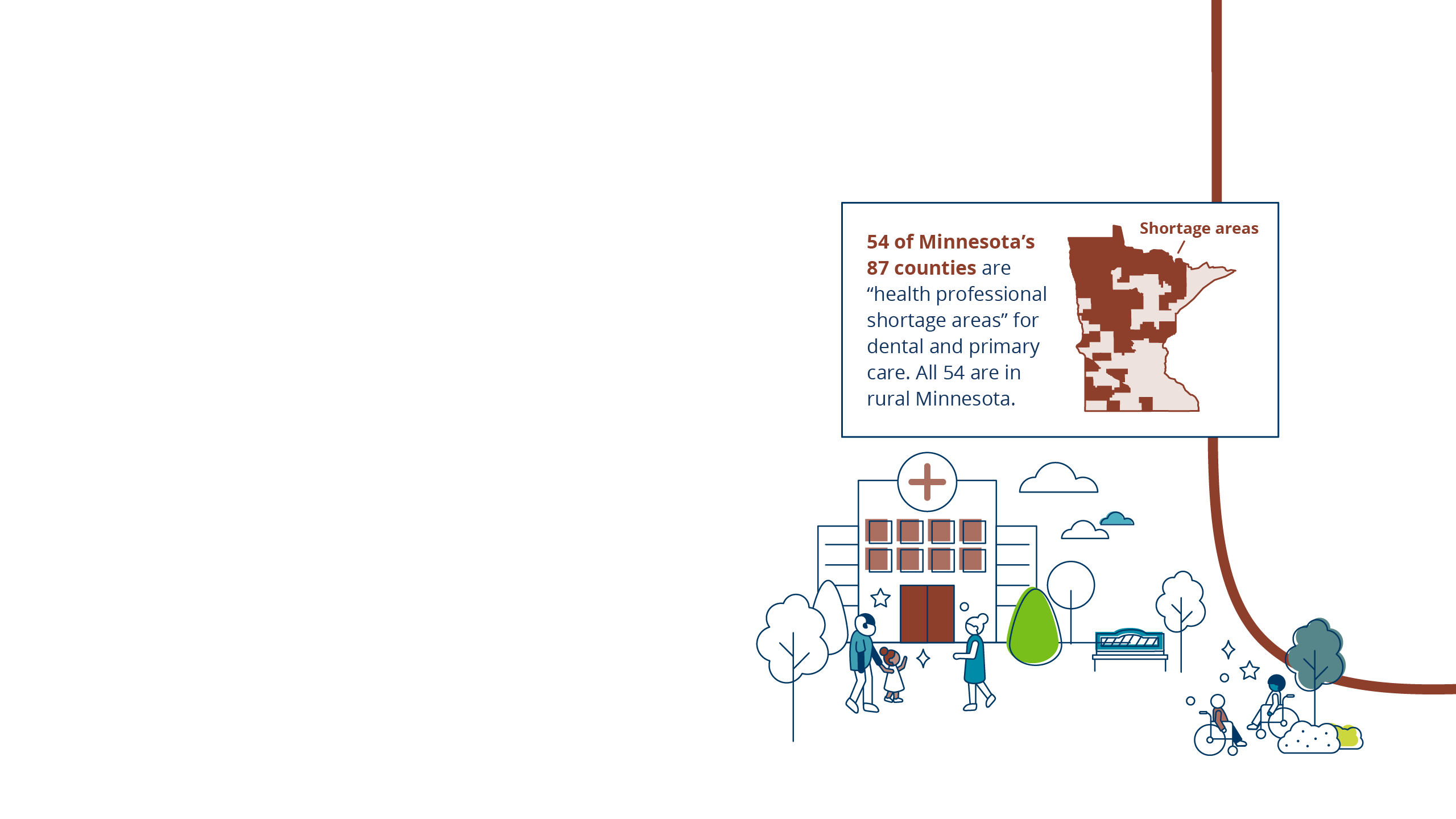

Finding and paying for healthcare is increasingly difficult. Rural Minnesota hospitals have been closing or limiting their services. Health expenses often eat up a significant portion of savings and Social Security benefits.4 Medicare is not enough, nor does it cover important items like dental, vision, hearing and long-term care.

Investing in a healthy older age for all Minnesotans will pay dividends in social capital and economic benefits.

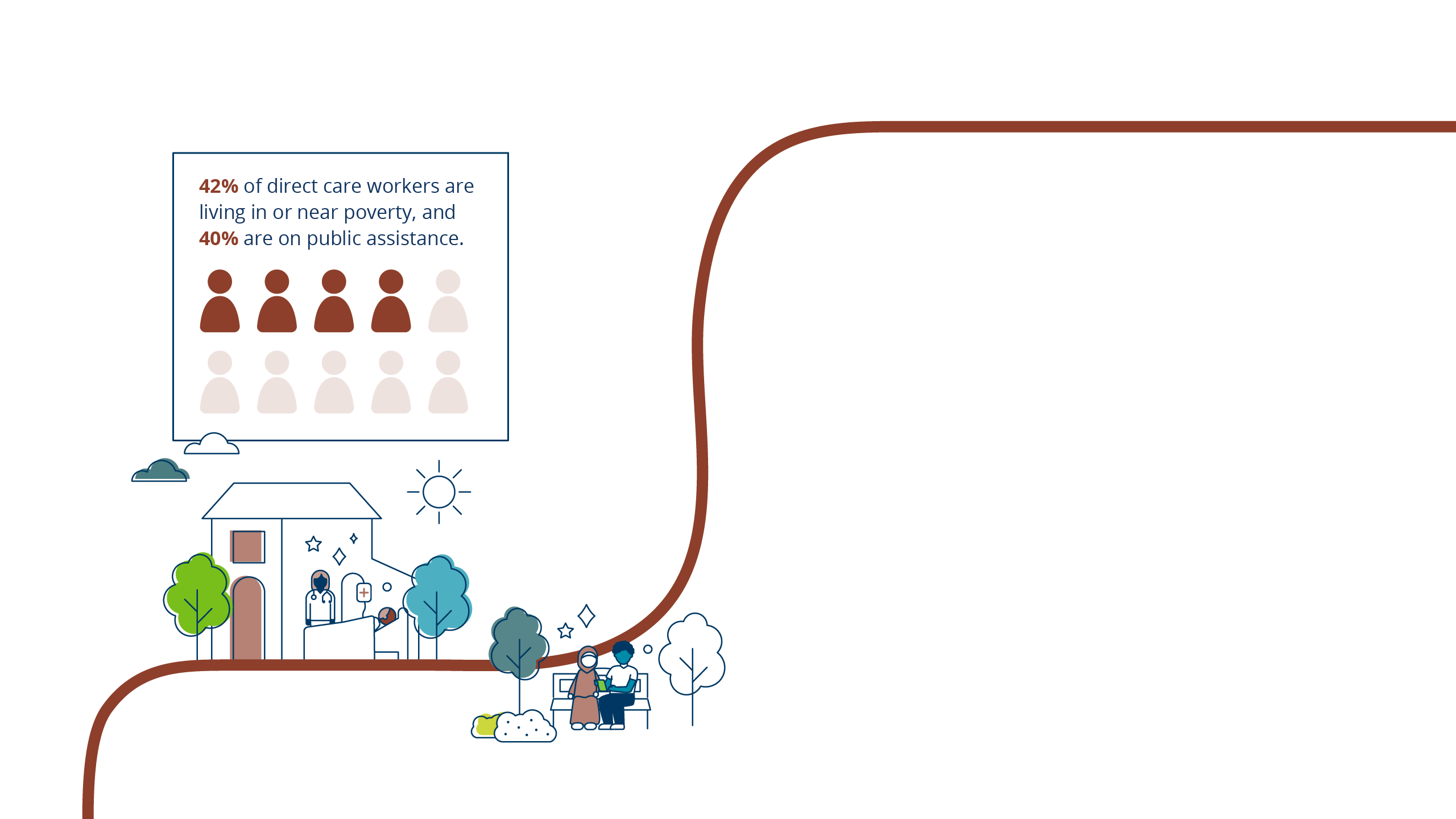

A Thriving Direct Care Workforce

Driven largely by massive workforce shortages, 450 older or disabled Minnesotans are denied admission to assisted living and skilled nursing communities every day.5 Dozens of nursing homes have closed, and more are considering closure. Greater Minnesota is most impacted.

Around 17,000 caregiver positions in Minnesota’s skilled nursing homes, and 15% of caregiver positions in assisted living communities, are vacant.6 Though absolutely essential, these demanding direct care jobs currently have little to offer—low pay, poor benefits, limited training and unpredictable hours. The workforce shortage also reduces the availability of in-home care services, on which there will be growing demand.

Bold investments are needed to address this workforce crisis and ensure our systems are ready for us when we need them.7

Featured Statistic Sources

Minnesota Health Care Disparities, Minnesota Community Measurement, 2021.

A. L. Brewster, M. A. Brault, A. X. Tan et al., “Patterns of Collaboration Among Health Care and Social Services Providers in Communities with Lower Health Care Utilization and Costs,” Health Services Research, published online Sept. 19, 2017.

AARP Public Policy Institute, Valuing the Invaluable, 2023.

Minnesota Department of Health.

Footnotes

1 AARP Public Policy Institute - Valuing the Invaluable, 2023.

2 Dementia caregiving in Minnesota, Alzheimer’s Association of Minnesota and North Dakota, 2021.

3 “Ageism Amplifies Cost and Prevalence of Health Conditions,” Becca Levy, et al. The Gerontologist, 2018.

4 “How Much Does Health Spending Eat Away at Retirement Income?” Center for Retirement Research, Boston College, 2022.

5 The Long Term Care Imperative, Financial Status Survey of Nursing Facilities and Assisted Living Facilities Survey, April 2023.

6 The Long-Term Care Imperative, 2024.

7 Linda Fried, “Investing in Health to Create a Third Demographic Dividend,” The Gerontologist, 2016.

About Age-Friendly Minnesota

Age-Friendly Minnesota is a collaborative statewide effort to make our systems and communities more inclusive of and responsive to older adults.